Paving the Path to Leadership: Who Gets Promoted to Managerial Roles?

A star individual contributor consistently outperforms, yet remains in the same role year after year. Meanwhile, a fresh graduate rockets into a manager position within two years. What separates those who make the leap into leadership from those who don’t? In this post, we examine data from the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (a long-term study of life in Australia) to identify factors that predict who rises to managerial roles, and how long that rise takes.

Climbing the Ladder to Leadership – What the Data Shows

Drawing on data from 8,830 full-time workers tracked since 2001, we examined promotions to management roles (e.g. becoming a supervisor/manager) and the factors that predict them. For this analysis, we specifically focused on employees who started in non-managerial positions, tracking who was promoted to management over time (as opposed to employees who were already managers at the start of the survey period). The analysis considered education level, age, gender, and their interactions, effectively comparing employees with similar profiles in order to isolate the effect of each factor in question.

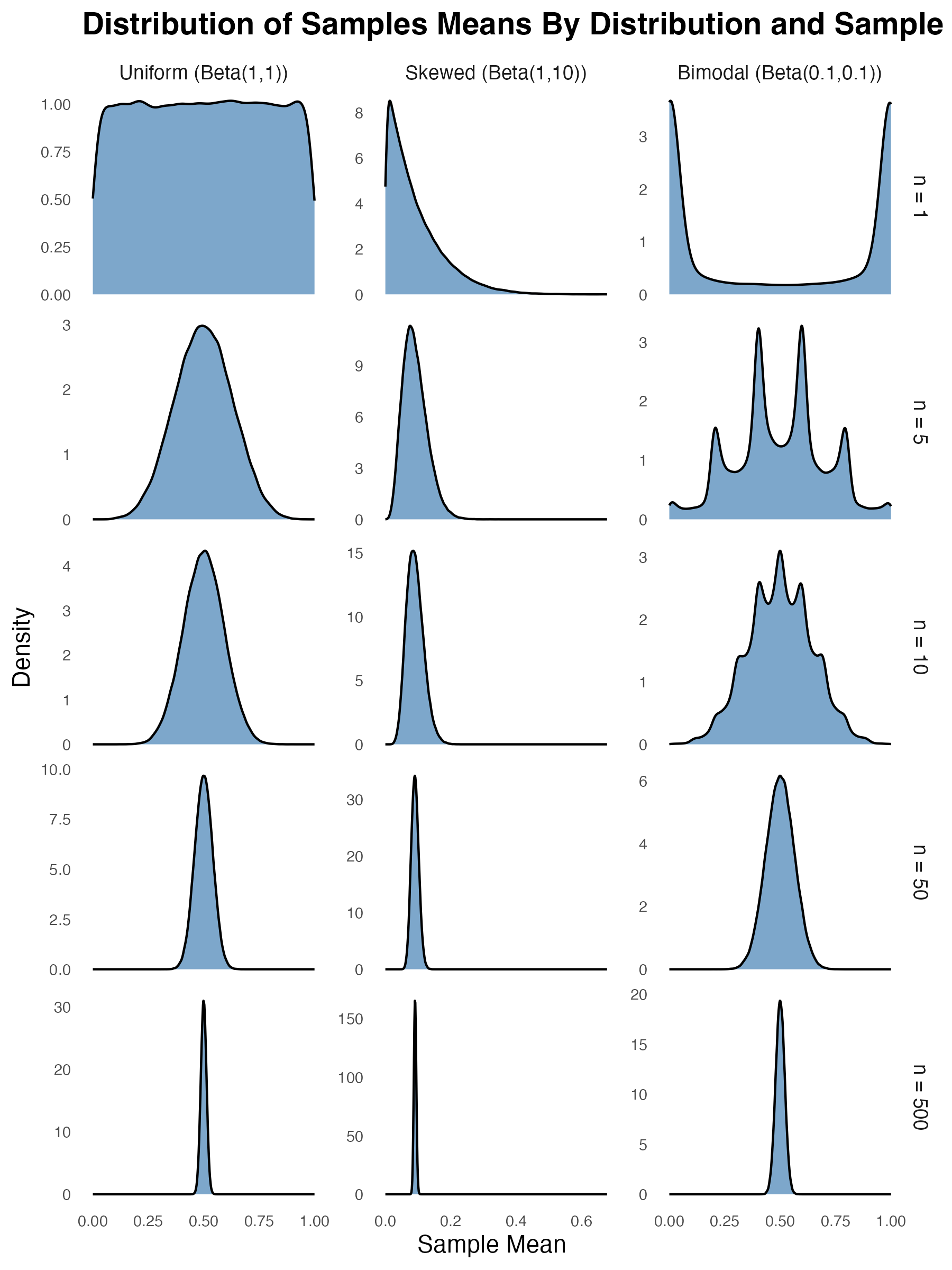

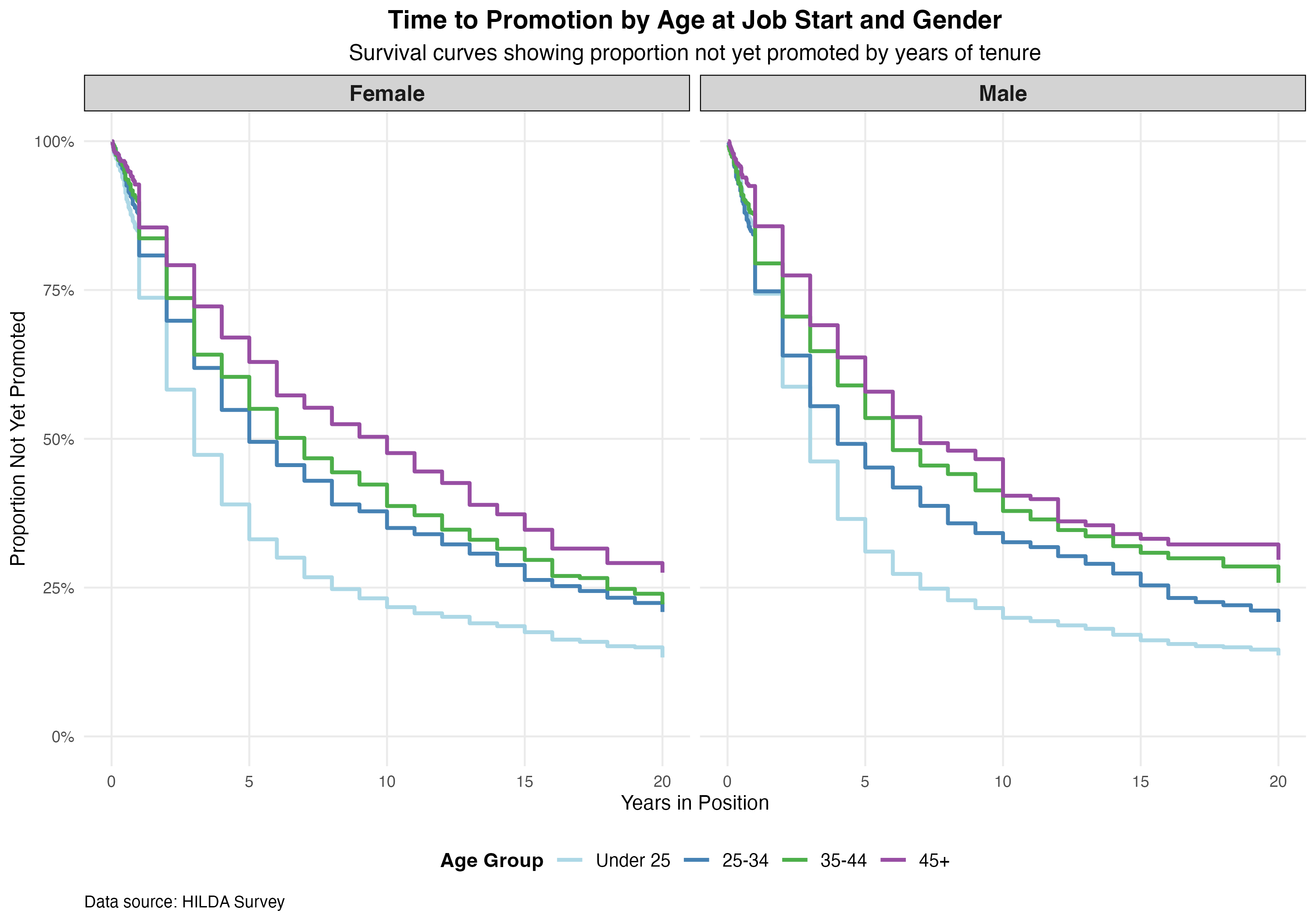

The survival curves below illustrate the journey to management for different demographic groups, with separate panels for females (left) and males (right). Each line tracks a different age cohort’s progression into leadership positions over time. The vertical axis shows the percentage of employees not yet promoted to management, while the horizontal axis tracks organisational tenure. Steeper downward slopes indicate faster promotion rates.

The visualisation reveals several interesting patterns. First, promotions to management typically occur within the first 5-10 years of tenure. By the 10-year mark, across all age and gender groups shown in the figure, 50% or more of employees have been promoted to management positions. After this period, the curves flatten, suggesting that if you haven’t moved into leadership by then, you’re much less likely to do so later.

Perhaps surprisingly, younger employees (represented by the steeper lines) tend to be promoted to management more quickly than their older colleagues. This age disparity could reflect several factors: younger employees might be working in fast-growing sectors with more upward mobility, or they might be specifically recruited into roles with clear advancement tracks. Alternatively, this pattern may indicate a selection effect - employees who begin their tenure at older ages without being managers may already be on specialist or technical tracks where leadership roles are less common. Remember, these curves track people who all started in non-management positions.

When comparing the left and right panels, we observe remarkably similar patterns between men and women. This suggests that when controlling for age and education, gender plays a relatively minor role in determining who gets promoted to management and how quickly that happens.

While not included in the graph, our broader analysis also found that education level was a significant predictor of promotion speed. Employees with Bachelor’s degrees or higher education tended to be promoted to management positions sooner than those without those educational qualifications.

Building Your Leadership Pipeline: Practical Takeaways

For HR and leadership development professionals, these insights highlight a few action areas.

First, identify and cultivate early-career high performers. Given that future leaders may emerge in their 20s and early 30s, make sure your organisation has mentoring, fast-track programs, or stretch assignments to nurture young talent. Early identification of leadership potential can help accelerate development so that those individuals are prepared when leadership opportunities arise.

Second, the gender parity in promotion rates is encouraging – maintaining this requires ongoing commitment to bias-free promotion practices. Ensure that your talent identification processes are equitable and that support (like flexible work arrangements or return-to-work programs) is in place so that women’s early-career gains are not derailed by life events. That being said, it doesn’t appear to be the case that this parity in promotion rates equates to parity in income over time (see my earlier post on parenthood and the gender pay-gap here). So there’s a lot more work to be done. Organisations should regularly review compensation practices across management levels to ensure equity in pay, not just in title advancement. Pay transparency, structured review processes, and clear compensation bands can help address the persistent earnings gap that exists even when promotion rates are equal.

Third, invest in education and skill development across your workforce. Our analysis shows that formal qualifications significantly increase promotion chances. Rather than limiting your hiring pool to candidates with advanced degrees, consider creating pathways for promising employees to gain additional qualifications through tuition assistance programs, industry certifications, or university partnerships. By investing in employee education, you’ll naturally expand your pipeline of management-ready talent while fostering loyalty among ambitious team members.