Motherhood Penalty vs Fatherhood Bonus: How Does Parenthood Change Earnings Trajectories?

Having children changes everything - including, often, our relationship with work. While the personal adjustments of parenthood are well documented, we’re only starting to understand how parenthood shapes long-term career trajectories. How do earnings patterns shift after welcoming a first child? Do these changes differ depending on the gender of the parent? And what might these patterns tell us about workplace dynamics and career development?

What the Data Show: Parenthood, Gender, and Income

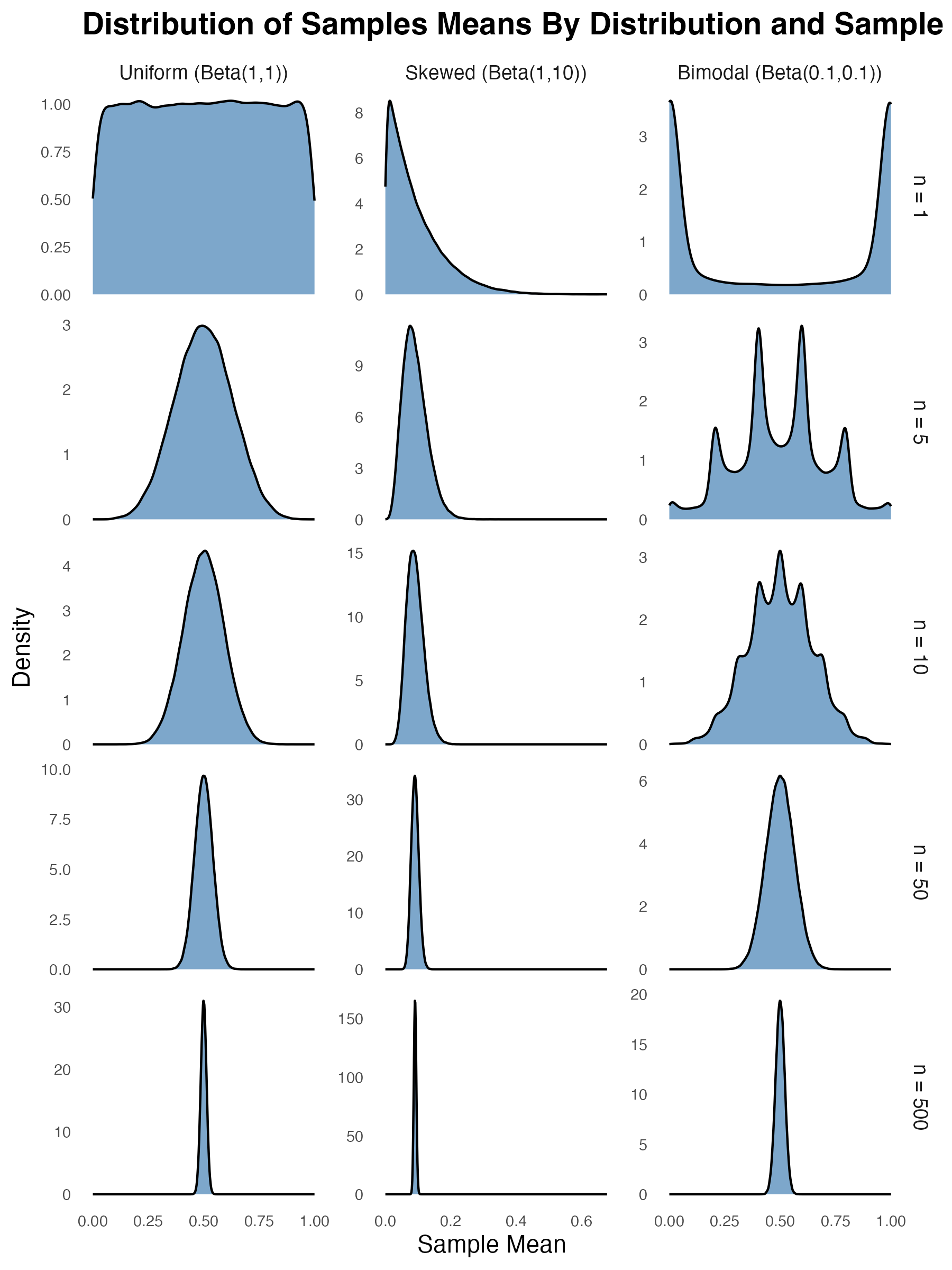

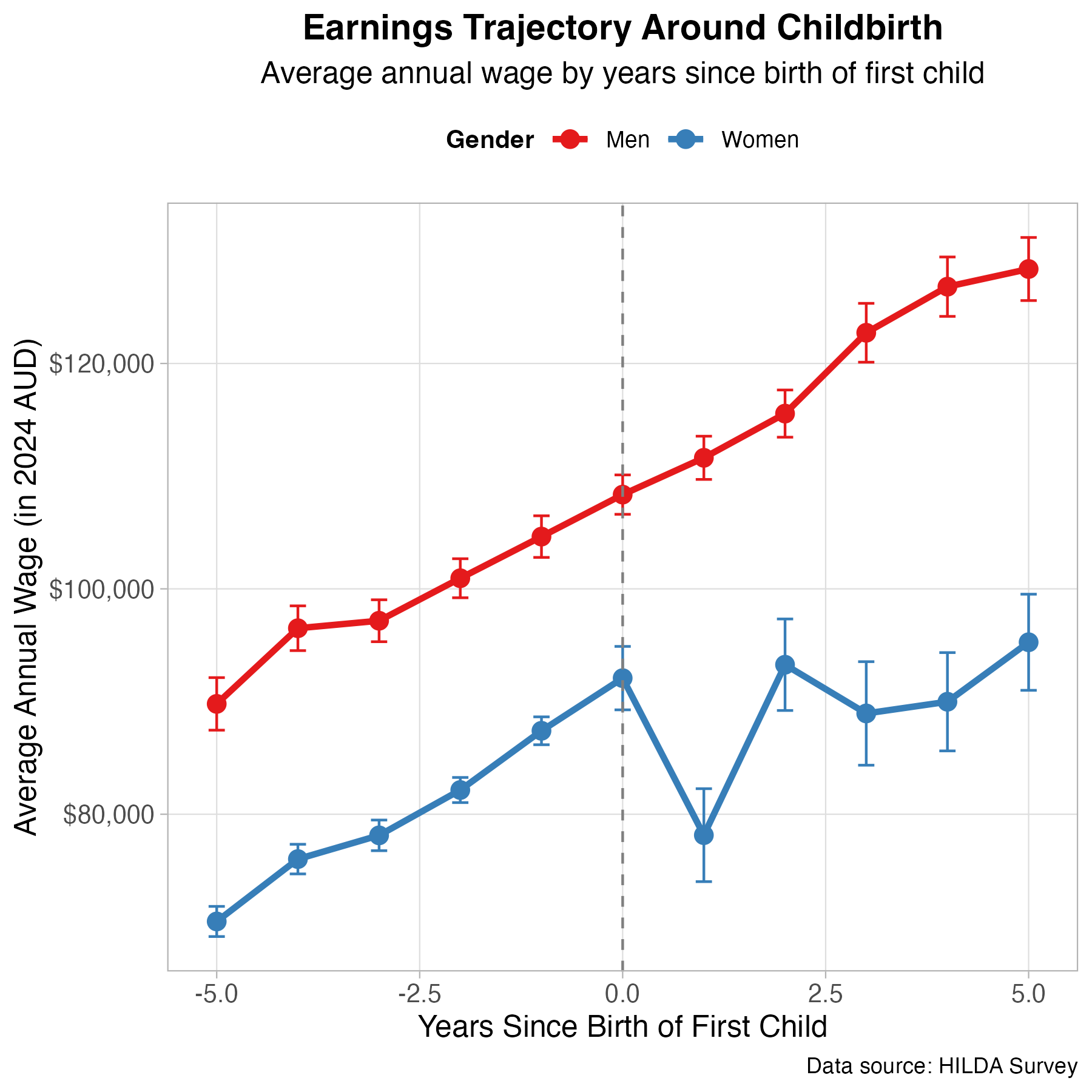

We used data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey to track wages from 3,546 men and women in full-time work in the years before and after they became parents (specifically, their first child’s birth). All earnings are adjusted to 2024 dollars to allow meaningful comparisons across time. Even before parenthood, our data showed a gap – men were earning more than women on average, reflecting the broader gender pay disparity. The figure below illustrates how this gap changes after becoming a parent:

Average annual wage trajectories are shown for men (red line) and women (blue line) in the years before and after the birth of their first child (year 0 = birth of first child). Men’s earnings show a steady upward trend through the transition to parenthood. Women’s earnings rise before the child, peaking around the birth year, then drop sharply in the year after childbirth (blue dip), and only partially recover in subsequent years. Even five years later, mothers on average earn significantly less than fathers, and the gap is larger than it was before children.

This pattern aligns with broader research findings: women typically lose around 4% of hourly wages per child, while men gain about 6% for becoming fathers. The year immediately after childbirth is particularly challenging financially for women, and though mothers’ wages recover gradually, they never catch up to their pre-children trajectory. By five years into parenthood, women’s pay often returns to its pre-children level, but by that time fathers have moved significantly ahead.

In our data, fathers were earning about 30% (approximately $30k) more per year on average than mothers by five years after becoming a parent – a much larger gap than the one prior to parenthood. One Australian study found that in the five years following childbirth, women’s total earnings were 55% lower on average than they would have been otherwise, while men’s earnings were not significantly affected.

Importantly, this isn’t just due to mums working part-time or taking time out. Even among women who maintain full-time employment, the penalty persists. Research shows that even when controlling for equivalent qualifications, experience, work hours, and job type, having children still reduces women’s earnings compared to women without kids. Meanwhile, men’s earnings don’t just continue unaffected – some studies find they actually accelerate after fatherhood, creating what researchers call a “fatherhood bonus.” Employers may (consciously or not) view fathers as more stable and committed breadwinners. For mothers, unfortunately, the opposite assumption often holds – they’re perceived as less committed to work, which can hinder promotions and raises, compounding the income loss beyond the time they actually take off.

Implications for Employers and Policy Makers

The persistence of this gendered career impact has direct implications for businesses and policy makers focused on retention, talent development, and equity. Here are a few key areas to consider:

Support working mothers with flexibility

Organisations that want to retain talented women need to make it feasible for new mothers to stay and progress. This includes offering truly flexible work arrangements, hybrid/remote options, and robust parental leave. Critically, it also means providing or subsidising childcare support, because affordable childcare is often key for a mother’s ability to continue her career.

However, simply having maternity leave isn’t enough – if there’s no support when she returns, her long-term earnings will suffer. Flexible schedules or part-time ramp-back periods can help mothers remain on track instead of stepping off completely.

Encourage and normalise paternity leave

One way to address this “motherhood penalty” is to balance the load. When fathers take substantial parental leave and share caregiving responsibilities, it can improve the mother’s transition back to work. Organisations should not only offer paternity leave but also actively encourage men to use it. This sets a cultural tone that parenting is a shared endeavour.

Over time, if it becomes routine for dads to also take time off for family, employers will be less likely to view young mothers as uniquely “risky” hires or promotions. Normalising fathers being out of office for family can help level the playing field for mothers.

Re-evaluate advancement and pay practices

Organisations must ensure that having a child does not derail a high performer’s career. Review your promotion and raise cycles with an eye on new parents – are you inadvertently overlooking someone because they had a few months away or came back on reduced hours temporarily?

Guard against bias in performance evaluations; for example, avoid penalising an employee for a lighter client load during their leave period when considering them for advancement. Some companies establish “returnship” programs or mentorship for employees coming back from parental leave, to integrate them and get their career momentum back.

The bottom line is to proactively counteract the loss of visibility and opportunities that often hits new mothers. By intentionally supporting their career growth (through training, clear paths to promotion, and fair pay reviews), employers can mitigate the long-term wage penalty these women would otherwise face.

From a policy perspective, the findings highlight that achieving gender pay equity will require systemic changes. Paid parental leave, broadly accessible childcare, flexible work cultures, and legal protections against caregiver discrimination are all important. The fact that women earn significantly less than men after having children is not just a family issue – it’s a productivity and talent issue for businesses, and an economic issue for society. Bridging this gap is important for achieving higher workforce participation and reduced attrition of skilled women.